I. Leo Glasser served in the U.S. Army from 1943-1946.

In this interview, U.S. District Judge I. Leo Glasser of the Eastern District of New York recounts his World War II combat experience and subsequent judicial career. Judge Glasser, who sits in Brooklyn, served in the U.S. Army from 1943-1946, retiring as a Tech Corporal.

WWII Highlights:

- Served in France and Germany in 1944-45 in a mobile, half-track anti-aircraft battalion.

- Arrived at Dachau concentration camp after its liberation.

- Received a Bronze Star.

Transcript

Q. Can you tell me about your early years, before World War II?

A. I was born on the lower east side of Manhattan, where I grew up and graduated high school at a relatively early age. I started City College and attended City College for a year during the day. Then, my parents could not afford to keep me in City College, so I went to work at the age of 16 and continued City College at night.

I began to work as a copy boy for the Journal American, and was there for nearly two years. I had, when I was drafted, the title of Junior Editor of the Sunday Journal American, which was a euphemism for exalted copy boy.

I wonder how many of us who were in the Army really understood what we were fighting for, or who the enemy really was. —Judge Glasser

Before I was drafted – for reasons which I don’t understand and can’t really recapture – I thought I wanted to be a lawyer. In those days, it was possible to start law school if you had completed two years of college. So, I applied for admission to the evening division of Brooklyn Law School. I managed to complete one semester and then was drafted and served close to three years in the service. I don’t know that most persons serving our country had any great thoughts of patriotism. You were drafted, and you were joining the army not because you were volunteering but because that is what you were called upon to do. I don’t recall having any exalted notions of entering upon some sacred patriotic duty.

Q: Tell me about your Army service in Europe.

A. We landed in England. We were in a little town called Leek, where we were preparing for crossing the channel going into Europe. We arrived in France close to June 6, maybe a couple of weeks thereafter. We spent a little bit of time in a town called Sainte-Mere-Eglise. We were there not terribly long and then proceeded to make our way clear across France. We crossed the Rhine at Metz and got into combat at that point.

I spoke what passed for German. I think there was probably more Yiddish than German, but I was able to communicate quite well with Germans when that was necessary. The captain of our battery, his Jeep driver, and I would – as we moved along across Germany – would go ahead on forward reconnaissances for the purpose of setting up command posts.

One of the things that stands out in my mind were the excited denials the Germans made that they had anything to do with the Nazis when we requisitioned their homes for a command post. On occasion [we went] through things which were lying on tables, going through photo albums and seeing pictures of their sons standing over desecrated Jewish tombstones in cemeteries.

But looking back, one of the things which I find astounding was that there wasn’t any knowledge or indication that I had during those years in Europe of such a thing as a concentration camp. I wasn’t aware of it at all. I didn’t know of such a thing until we got to Dachau. I wasn’t one of the liberators of Dachau. I got there sometime after Dachau had been liberated. I saw the crematoria and the ovens and the barb wire trenches. Until then, I had no idea. I don’t recall reading anything about it in the Army newspapers. Looking back on it, I find that astounding. I wonder how many of us who were in the Army really understood what we were fighting for, or who the enemy really was.

Q. What were the circumstances surrounding your Bronze Star?

A. I was recommended for the Bronze Star by the captain of my outfit. The Bronze Star was awarded for extraordinary service. I don’t know that I was particularly brave or did anything spectacular.

There was one occasion which I recall from time to time. Captain Price, a driver, and I were way ahead of the infantry at one point, and we had stopped on a road, just looking around determining where we might place some half-tracks. The Germans had created trenches along roads, and there were German soldiers in those trenches. As we were stopped – the three of us – just looking around the countryside, a couple of Germans popped out of one of those trenches behind us, and they could very easily have killed all three of us. But they jumped out and put their hands up. I guess having seen American soldiers arriving at that point, it must have crossed their minds that maybe the jig was up for them. That was a rather frightening incident. Why they didn’t kill the three of us – which they could have done very easily – I don’t quite understand to this day.

Q. Did anything else notable happen while you were overseas?

A. When the war ended, the army had a program which permitted those who believed they were qualified to apply to European universities. I spent one semester at the law school at the University of Birmingham, which was a wonderful experience. It was there that I was discharged from the army.

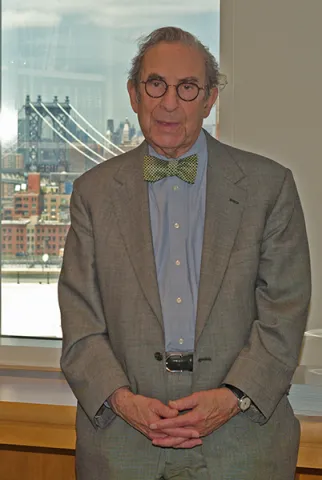

Judge I. Leo Glasser. Photo courtesy of Judge Glasser.

Q. How were you changed by the war?

A. I was obviously more mature, in the sense that the experience of living with people from remarkably different backgrounds was a growing experience. I don’t know that I was aware of it or thinking of it, but the fact of the matter was that I managed to survive, living under difficult circumstances for close to two years.

When I returned, I started law school again but this time during the day, thanks to the GI Bill. I did very well academically. My mindset when I started law school after the war was that this was going to be my job. I was going to go to school from 9 to 5. When classes were over in the morning, I’d go to the library, and I’d just stay in the library until 5. I managed to acquire a pretty good academic record. It was virtually all A’s. The law review had been suspended during the war, and the dean wanted to get it started again. I was asked to become the editor-in-chief. That was an interesting and difficult job, to start a law review virtually from scratch.

Shortly before I graduated, the dean called me in and asked me if I would like to stay on for a year, emphasizing that it’s only for a year, as a teaching fellow. Law schools were crowded with soldiers coming back with the GI Bill, and Brooklyn Law School was not any different. An enlarged faculty was needed. Having nobody in my family who was a lawyer and having not even begun to look for a job, I said yes. Toward the end of the first year, the dean called me in and asked me if I’d like to stay on for another year, emphasizing again, “It’s only for another year, but you’ll stay on as an instructor,” which I did. At the end of that year, he said, “You can stay here as long as you like,” and that’s where I stayed until 1969, when Mayor Lindsay called and asked if I’d be interested in appointment to the family court, where I then spent the next eight years.

Q. How did family court differ from U.S. District Court?

A. If a court is to be measured by the impact that it has upon the lives of people, the family court is the most important court that one can possibly imagine. I like to think of the family court as the social emergency room. It really is to society what the emergency room at Bellevue Hospital is to society.

The first time I removed a child from a mother, I was very new to the family court. After I issued an order having the child removed because the child was badly neglected, I remember leaving the courtroom and literally crying like a baby. I couldn’t imagine what I had just done. I took a child away from a mother. How could I do that? My mind was filled with thoughts of 9 months of pregnancy and labor pains.

Q. Do you have any specific memories of the case involving John Gotti, the mobster?

A. It was a high-profile case. I had the mindset, as I got up each morning, that this is just another criminal case. It’s going to be tried as best as I can try it, paying attention to all the due process and other procedural rights which he has, as any other defendant would have. People would line up outside the courthouse at 4 o’clock in the morning to get into the courtroom to attend the trial. But that was my mindset trying the Gotti trial – treat it just as another criminal case.

Q. What do you take the greatest pride in, looking back both at the war and your later career?

A. I’m happy that I have been able to live a life which I think has been productive and conscientious. Doing what I was assigned to do, doing the best I can, and discharging my responsibility for whatever job I was doing at the time is satisfying to look back on.

Q. Why do you continue to work full-time on the bench?

A. Well, to begin with, I love the law. The United States District Court is without any doubt the greatest court in the world, in the sense that it deals with everything from admiralty to zoning – every conceivable aspect of the law. Also, if senior judges all decided to go fishing, I think the federal judiciary would be in a great deal of difficulty. I don’t remember the percentage of federal cases that senior judges deal with, but it’s substantial. We perform a significant service to the judiciary, and to the country by extension.

Subscribe to News Updates

Subscribe to be notified when the news section is updated.