On June 7, 1944, Dickinson Debevoise was part of D-plus-one, a tidal wave of men and machinery pouring onto Normandy’s shores just a day after D-Day. Even when a mine struck his ship, Debevoise was barely slowed. Within weeks, he was building bridges essential to the invasion of Nazi Germany.

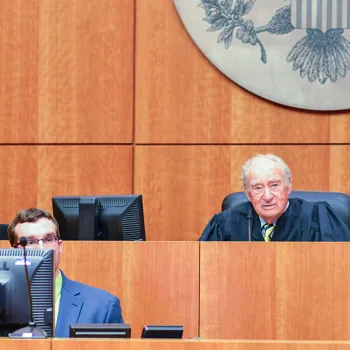

Today at age 90, Debevoise continues to serve his nation, as a U.S. District judge in Newark, N.J. Within the federal judiciary, he is far from alone.

Seventy years after D-Day, whose anniversary was commemorated on June 6 in France, the "Greatest Generation" is fading rapidly from the nation's leadership—with the last two World War II veterans to leave Congress later this year. But the federal courts are a striking exception.Almost 70 World War II veterans continue to serve as senior-status federal judges. Although nearly all were eligible to retire on full pay two decades ago, many carry active and sometimes full-time work loads, even in their late 80s and early 90s. They cite their love of the law and a continuing call to service.

"It’s a performance of a duty, the same as I was doing when I was in Europe.” said U.S. District Judge Tom Stagg, a former Army infantry captain who sits in Shreveport, La. “I was appointed for life and I’m going to serve out my term.”

While differing on whether they like the term “the Greatest Generation,” and on whether the war influences their work on the bench, most judges agreed in interviews that they lived in an extraordinary time and still share a special bond.

“We are a brotherhood,” said U.S. District Judge Leonard D. Wexler, one of five World War II veterans who serve as senior judges in the Eastern District of New York. “We went through an experience which is unique. We may disagree philosophically, or on the law, but we still consider ourselves brothers.”

As young men, few envisioned themselves as future judges, and for some, even college was a stretch. They simply knew their country needed them. S. Arthur Spiegel, a U.S. district judge in Cincinnati, memorized an eye chart so the Marines would accept him. Debevoise promptly enlisted in the Army after the Navy turned him down.

“Everybody wanted to get into the war in some way or another,” Debevoise said. “It was a vast feeling. You just had to go into something.”

Of the World War II veterans who are still senior judges, at least two dozen saw combat in the Army, Navy, Marines and Army Air Forces. In recent interviews, many described close calls.

Stagg, an Army infantry officer, was shot in the chest while moving at night behind enemy lines near the French-German border. Almost miraculously, a pocket bible slowed the bullet enough that he could walk two miles to get medical attention.

Arthur L. Alarcon, a U.S. Court of Appeals judge based in Los Angeles, spent a day pinned down by machine gun fire in snow and a pool of frigid water in Germany. Only a doctor’s experimental treatment saved his legs from amputation.

As a submarine officer in the Pacific, U.S. District Judge Jack B. Weinstein, of Brooklyn, felt his craft struck by a Japanese vessel trying to ram it. The periscope was badly bent, but the sub survived and completed its dive.

Even as most were naturally frightened, some judges said they were aided by the confidence of youth.

Spiegel, a Marine artillery officer in the Pacific, had to crawl through surf and jungle undergrowth to rescue a wounded Marine while under Japanese machine gun fire.

“Of course we were all terrorized in those situations, but then we learned that we could handle ourselves and survive if we followed our training,” said Spiegel. “The first time around, you just don’t think you’re going to get hit, it’s going to be somebody else. So I was just doing my job of dragging this fellow out.”

As the war came to a close, the judges' lives were dramatically transformed, by their military experience and by the GI Bill of Rights, which paid for college education.

Weinstein, who before the war worked on the Brooklyn docks to pay for night school, graduated from Columbia Law School. Within a few years, as a Columbia law professor, he was helping Thurgood Marshall’s legal team in Brown v. Board of Education. Of his time in the Navy, Weinstein said, "I was proud ... to participate in what I then considered, and still consider, a great war for freedom."

Alarcon, who dreamed of law school but had no way to afford it before the war, became a Los Angeles County prosecutor. He helped secure a landmark first-degree murder conviction of a man whose wife’s body was never found.

For some, the war also brought critical changes in self-image, Wexler, who received two Bronze Stars and a Purple Heart, always thought of himself as a good athlete but a poor student until Army life convinced him he should attend college. To his surprise, Wexler loved law school, then litigation, then serving on the bench. At 89, he works five days a week and carries a full caseload.

“I had no idea I’d want be a federal judge. I never thought of it, I never wanted it. Guess what, I love it,” Wexler said. “It’s amazing how things happen without you expecting them. You’ve just got to go with the flow. Life has its crazy turns.”

Stagg proudly wears a miniature combat infantry badge on his suit lapel. But he says the war has little effect on his current work as a judge.

Others, though, do see an influence.

Weinstein, who enjoyed the informal style among submarine officers, never wears a judicial robe in the courtroom and often sits among jurors to better understand what they are seeing. He also said the war taught him how to be in “full command of that courtroom.”

Several judges said the simple fact of being thrown among so many different types of people had a lasting impact. Alarcon said his exposure to both courageous and frail human beings made him less hasty to judge those facing him in court.

“I think those of us who were in World War II have had a special experience. And one of the things that I really found amazing is how men could work closely together, and take care of each other and leave nobody behind,” Alarcon said. ”I think that experience, of dealing with total strangers from all over the United States, has given me a respect and compassion for my fellow human beings.”

Though many judges cited love of the law for why they continue to work, the spirit of service so prevalent during the war also plays a role.

“I’m very big on duty,” said Judge Stagg, of Louisiana. “I was given a duty by President Nixon, and I have done my damnedest to carry it out for the 40 years I’ve been here.”

Spiegel, who as a lawyer sued in federal court to desegregate Cincinnati swim and athletic clubs, candidly says that “it keeps me alive. How many people do you know who retire and have nothing to do? Two or three years later they’re gone.”

District Judge I. Leo Glasser, of Brooklyn, said, "To begin with, I love the law, and the United States District Court is without any doubt the greatest court in the world, in the sense that it deals with everything from admiralty to zoning."

Glasser also noted that senior judges handle a significant portion of the national caseload. "If senior judges all decided to go fishing, I think the federal judiciary would be in a great deal of difficulty."

One of the liveliest debates among the judges is whether they are part of a “Greatest Generation.” While several proudly claim the label, others note that every generation, including theirs, has its strengths and weaknesses.

But the judges agreed that World War II was an extraordinary time for this nation, and for those who lived through it.

U.S. District Judge Arthur D. Spatt, of Long Island, said that includes not just the soldiers who fought, but the women who worked in factories, and the civil defense wardens at home.

"I think the greatest generation was this country as a whole,” Spatt said. “It was united. Everybody worked toward one goal. Everybody participated with a full heart, and no dissent. When in the history of this country does this ever happen?"

Subscribe to News Updates

Subscribe to be notified when the news section is updated.