Judge Royce C. Lamberth served as an Army JAG Corps lawyer in Vietnam. He was appointed a federal judge in 1987.

Every Nov. 11, America honors the veterans who served this nation. Within the federal Judiciary, many judges have a special link to one part of the military: the Judge Advocate General’s Corps — better known to many as JAG.

The JAG Corps provides judges, prosecutors, and defense lawyers to administer the U.S. military justice system, whose roots date back to the Revolutionary War. More than 65 federal judges (about a quarter of all federal judges with military experience) list time in JAG.

Five veterans share their memories of the JAG Corps:

- John S. Cooke, Director of the Federal Judicial Center

- District Judge Stephanie L. Haines, Western District of Pennsylvania

- District Judge Royce C. Lamberth, District of Columbia

- District Judge Carlos E. Mendoza, Middle District of Florida

- Circuit Judge Carl E. Stewart, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

In interviews, four federal judges and one high-ranking Judiciary official also said the JAG Corps transformed their legal careers, giving them exceptional responsibility and mentorship when they were barely out of law school.

“I tried unbelievable trials, and got fantastic experience in JAG,” said Judge Royce C. Lamberth, of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia. He tried 300 cases, including many in combat zones in Vietnam.

Everyone interviewed said their JAG experience shaped their values and legal career.

“I loved putting on that uniform. It humbled me every time I did it,” said Judge Stephanie L. Haines, of the Western District of Pennsylvania. “It was just the honor of a lifetime to say that I supported and was a very small part of the military in service to our country.”

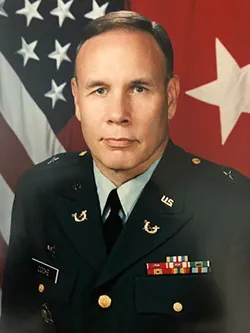

John S. Cooke, Director of the Federal Judicial Center

John S. Cooke, director of the Federal Judicial Center

Few Americans have greater insight into the military and civilian justice systems than John S. Cooke. To his own surprise, he rose to brigadier general and the top U.S. Army JAG Corps lawyer in Europe, and today he is director of the Federal Judicial Center, which conducts research and training for the federal Judiciary.

Cooke says the mission of the Army and that of the justice system go hand in hand.

“If people were perfect, we wouldn’t need law and we wouldn’t need armies,” Cooke said. “The army’s mission is to fight the nation’s wars and defend the country. But an unstated part of that mission is to do so in ways that are consistent with the law. If we don’t do that, then what we are defending is going to fall apart from within.”

A self-described amateur historian, Cooke notes that America’s military justice system dates back to the Revolutionary War. Since 1950, the military justice system has been governed by the Uniform Code of Military Justice. While the system has many parallels to the civilian justice system, especially in the areas of rules of evidence and standard of proof, there are distinct differences.

Commanding officers bring charges, convene jurors, and can reduce or even commute sentences. Personnel can be charged with such violations as insubordination or malingering.

When he entered the JAG Corps during the Vietnam War, Cooke recalled, “I had a three-year obligation, and my intent was to serve three years and zero minutes.”

Once in, he met young lawyers like himself, and supervisors steered him to a succession of challenging assignments. He became a teacher at the JAG school in Charlottesville, Virginia, then a military judge in Germany.

John S. Cooke retired as a brigadier general in the Army JAG Corps.

“It was one thing after another, where I had great bosses who gave me opportunities, which led to attractive job offers,” Cooke said. “I just sort of thought, I’ll do a couple of more years. Pretty soon it was a career.”

Army life surprised him in another way. His bosses cared about his well-being and that of his family. “I had seen the Army as a kind of a tough macho organization with cigar-chomping colonels,” Cooke said. “It really was a much more caring organization than a lot of corporations. That has carried with me.”

By the time Cooke left the Army and joined the FJC, in 1998, he had served as the chief judge of the U.S. Army Court of Criminal Appeals. But one of his favorite memories involved an enlisted man who lost his case and was sentenced to prison time in Fort Leavenworth and a bad-conduct discharge.

“After the trial, he told me he wanted to get back on active duty,” Cooke said. “My first thought was it’s a little late to be thinking about that now.”

But Cooke did some research and found there was a way to get a sentence remitted. He explained the process to his client, telling him that it started by being a model prisoner. A few years later, Cooke saw the defendant’s name in an Army Times newspaper article. The headline: “From Court Martial to Soldier of the Month.”

“If you hope to win a lot of acquittals, you’re going to be frustrated, but sometimes you can do a greater service in a different way,” Cooke said. “He did the work; I just did the research. But it was one of my prouder moments.”

Judge Stephanie L. Haines

U.S. District Judge Stephanie L. Haines for the Western District of Pennsylvania

U.S. District Judge Stephanie L. Haines, of the Western District of Pennsylvania, had no military tradition in her family, and as a second-year law student, she had zero expectation of signing up. That changed when a fellow law student invited a group of friends to hear a JAG Corps recruiter before they went out to dinner.

Sitting in a law school auditorium, Haines quietly became transfixed. “I thought, oh my gosh, this is exactly what I want to do,” she recalled. “It’s an opportunity to serve my country. This is where I really see myself.”

Haines was assigned to Fort Campbell, home of the 101st Airborne Division. “I was told, ‘You’re getting ready to enter the oldest, largest, and best law firm in the world’,” she said.

At 8:30 a.m., she was at her desk practicing law. But at 6:30 a.m., she was doing daily physical training like any other soldier.

“We were doing flutter kicks in the mud, running in formation, singing cadence, like what you see on TV,” Haines said. “I was rappelling out of helicopters. You were a lawyer, but you also had to perform well as a military officer.”

Judge Stephanie L. Haines retired as a JAG colonel in the Air Force reserve.

Like other JAG lawyers, her first assignment was providing basic legal assistance, such as drafting wills, for soldiers and their families. She next served as a prosecutor, then as a lawyer handling defense appeals. “I can’t say enough great things about the Army JAG Corps and the opportunities they gave me,” Haines said.

After she left full-time duty in 2002, Haines continued as a reserve while she worked as an assistant U.S. attorney, and later transferred to the Air Force reserve. Haines retired as a colonel in 2019, when she became a federal judge.

She remains moved by the spirit she saw, especially among young teenage recruits ready to sacrifice their lives.

“I will say that the 24 and a half years I wore a uniform were absolutely the pleasure and honor of a lifetime,” Haines said. “I was able to serve with true American heroes. People who everyday were duty bound, were loyal, were selfless, courageous men and women who wore that uniform and were willing to lay down their lives in a heartbeat, in defense of their country and in defense of the freedoms we all treasure.”

Judge Royce C. Lamberth

U.S. District Judge Royce C. Lamberth for the District of Columbia

U.S. District Judge Royce C. Lamberth freely admits he had no interest in joining the JAG Corps. Yet it led to his favorite job ever — and no, he does not mean his current position as a federal judge in the District of Columbia.

Lamberth was drafted in 1967, just as he was graduating from law school. He was reluctant to accept JAG’s required four-year commitment until he realized he was headed for infantry duty. “It was the height of the Vietnam War. Suddenly the JAG Corps didn’t look so bad,” he said.

While the country and the Army were under growing strain, Lamberth found the JAG Corps to be a young lawyer’s dream. “I ended up getting unbelievable experience in JAG. My first trial was a first-degree murder trial. I tried 300 cases in JAG, including six murder trials. I loved my time in JAG Corps, after going in kicking and screaming.”

He did not avoid Vietnam, however. After starting at U.S. installations, Lamberth eventually served in Cam Ranh Bay and the Mekong Delta. The bases were shelled at night, and most days, Lamberth flew by helicopter to hold trials in advance fire bases in hostile territory. It led to extraordinary pressures on the military prosecutor and judge, who flew with Lamberth to the fire bases.

“At the end of the day, you would want to get on the last chopper out. By 4:30, you would stipulate to just about any testimony,” Lamberth said. “You did not want to be on the fire base overnight. Sometimes the fire base could get overrun and everybody would be killed or wounded.”

Lamberth re-upped when his four years ended. At the Pentagon, he joined the litigation division for cases involving the Army in federal court. The unit helped shape new law — including a Supreme Court case that upheld disciplinary actions for behavior unbecoming of an officer. He also persuaded federal courts to uphold the administrative discharges of all soldiers involved in the My Lai massacre.

“These were tremendous cases,” Lamberth said. “It was the best job I ever had, to this day.”

Appointed to the federal bench in 1987, Lamberth presided over the trial of Blackwater Security contractors accused of killing 14 Iraqi civilians in 2007. He sees a close tie between the military’s mission of defending our country and the Judiciary’s mission of upholding the law.

“It’s very important to civil society that we play by the rules and hold ourselves to a higher standard,” Lamberth said. “And we as a country have to do that. I thought it important in Blackwater, I thought it important in My Lai. We as a country, on Veterans Day in particular, need to be proud of what we’ve done.”

Judge Carlos E. Mendoza

U.S. District Judge Carlos E. Mendoza for the Middle District of Florida

U.S. District Judge Carlos E. Mendoza, who serves in the Middle District of Florida, is a first-generation son of naturalized citizens, whose father immigrated from Colombia and whose mother came from Honduras.

Mendoza enlisted in the Marine Corps after high school, serving in Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm. When he graduated from law school in 1997, he entered the Navy JAG Corps.

“I had a desire to continue serving,” said Mendoza, adding that his parents’ example prepared him for the military’s discipline and service ethic. “Growing up we were always reminded that in this country, unlike almost anywhere else in the world, ambition, hard work, and drive dictate what heights you will reach.”

The JAG Corps proved to be a tremendous platform for Mendoza’s legal career. “The mentoring of young attorneys/officers is second to none,” he said. “I was impressed that they not only wanted us to become capable attorneys, but honorable people, as well.”

Mendoza does have some criticisms of the military justice system, saying it is tilted against defendants. Commanding officers can bring charges and choose the jury, and only a two-thirds jury majority is needed to convict.

Years before he joined the federal bench, Judge Carlos E. Mendoza served as a Marine in Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm.

Nonetheless, “my time in the Marine Corps and Navy JAG Corps offered some of the most important lessons of my life,” Mendoza said. “I would not have arrived where I am at now, professionally or personally, had I not had the privilege of walking in the shadows of the many great men and women who gave me their time, friendship, and advice.”

Mendoza sees a close connection between his military service and his duties as a judge. “Lady Justice wears a blindfold for a reason,” he said. “Many men and women have risked and even sacrificed their lives to ensure that the blindfold remains intact.”

He remains grateful for what his military service gave him.

“I am the proud son of working poor immigrants that devoted their entire lives to their children,” Mendoza said. “Considering my humble beginnings, I have no business serving as a United States district judge, except of course in this political experiment of ours, an experiment certainly worth fighting for.”

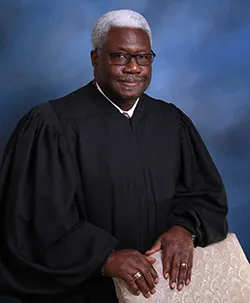

Judge Carl E. Stewart

Judge Carl E. Stewart, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

Judge Carl E. Stewart, of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, received his entire elementary and secondary education in segregated schools.

“It was just a tough time. I was growing up in a period with a lot of hatred,” Stewart recalled. “In school, we often had substandard equipment and books. I had hope that things would get better, but there was no real evidence they would get better.”

Stewart entered law school during the Vietnam war era. After learning that his low draft number would probably result in him being drafted while he was in law school, Stewart joined the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps. By graduating and passing the bar on his first try, he was able to join the JAG Corps as a captain, instead of as a second lieutenant in the regular Army.

“Suffice it to say, I had a lot of incentive to study hard,” Stewart said.

Like other JAG Corps veterans, Stewart was quickly thrown into representing clients. Among his clients at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio were soldiers in a severe-burn unit.

“I was a 24-year-old lawyer, green as the uniform,” Stewart recalled. “It was a growing up experience. There was no time to be nervous, no time to be scared.”

All JAG lawyers are officers; prosecutors and defense lawyers both wear the same uniforms, which sometimes posed a challenge, Stewart explained.

Judge Carl E. Stewart joined the Army JAG Corps as a captain during the Vietnam War years.

“You’re talking to a 19-year-old kid and saying anything you say to me is confidential. And that kid says, ‘How can I trust you if you have the same uniform on as the prosecutor?’,” Stewart recalled. “I’m thinking, ‘They didn’t teach me in law school how to cross this bridge.’”

The experience taught him a self-confidence that transformed his career. After the Army, he became a federal prosecutor and was encouraged to seek election as a Louisiana trial judge at age 35.

“I received an extremely valuable lesson in learning about preparation, professionalism, and presenting yourself,” Stewart said. “When I ran for judge, I knew that I could do the job.”

After later becoming a state appellate judge, Stewart was appointed to the U.S. Court of Appeals in 1994. In 2019, he received the federal Judiciary’s highest honor, the Edward J. Devitt Distinguished Service to Justice Award. “I was speechless,” he recalled.

For all his achievements, Stewart says providing service to the burn victims remains one of his greatest satisfactions.

“It drilled into me that being a lawyer is a service profession,” Stewart said. “Mine was a small part, but to know you brought satisfaction to these soldiers and their families, I can’t measure that.”

He added: “I’m proud to be a veteran. I really am. It’s a part of who I am, not just a period of time in my life. I have a flag on my house and it’s flying every day. I have great respect for our country and the honor of those who served.”

Subscribe to News Updates

Subscribe to be notified when the news section is updated.