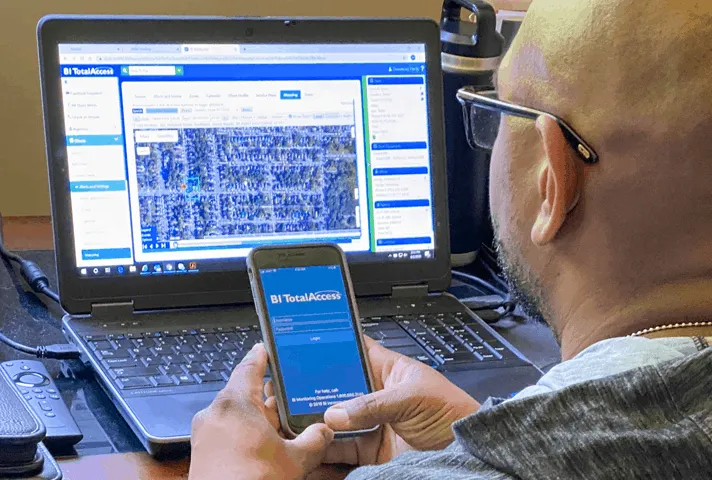

A probation officer in the Western District of Washington reviews the court’s judgment on a case he is handling from his home.

Chief Pretrial Services Officer Patricia Trevino, of the Eastern District of Michigan, thought she was prepared for the worst as the COVID-19 health crisis made its way to Detroit. But nothing prepared her for the emotional challenges ahead when several court employees tested positive for the virus or lost loved ones and needed to self-quarantine.

“I never imagined that Michigan would be one of the largest hot spots for the virus,” Trevino said. “It was stressful. Testing was scarce and several of us were in self-quarantine—me included—after experiencing COVID-like symptoms or coming into contact with someone who had.”

Probation and pretrial officers play a critical role for the Judiciary. They supervise people recently released from prison or awaiting trial to help them stay on the right side of the law – work that is best done in person. When the pandemic struck, officers had to find new ways to do their jobs almost overnight.

As the duration of the crisis grew from weeks to months, it became clear to Trevino’s pretrial unit, along with federal probation and pretrial offices nationwide, that many of their face-to-face approaches for investigating and supervising people needed to be replaced with digital alternatives to protect the well-being of officers, the individuals they supervise, and the public.

“We have chiefs and officers all across the country and their staffs who are innovating at a rate that is just incredible,” said John Fitzgerald, chief of the Probation and Pretrial Services Office at the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts (AO). “They are trying to balance the needs of the courts with the needs of the people they serve, while taking care of their own personal health and safety and that of their families. They are really innovating and thinking creatively to get us through this.”

When COVID-19 cases first appeared in the United States in January, Chief Probation and Pretrial Officer Connie Smith, of the Western District of Washington, quickly moved to organize regular calls with her fellow probation/pretrial chiefs across the country and with probation and pretrial officials at the AO. She realized that large-scale collaboration would be necessary to innovate and adapt to remote operations.

A probation officer in the Western District of Washington puts on protective gear before heading out into the field.

“About 70 percent of our work is in the community and there wasn’t any kind of playbook, guidelines, or rules for how to respond to a situation like this,” Smith said.

As a result of those early discussions, officers are better prepared to continue their investigative and supervision duties from afar by stepping up their use of technology.

Officers are conducting virtual home visits by using common video-calling applications, such as FaceTime and Google Hangouts. The apps allow them to check in with people under supervision and take a tour of the residence with a smartphone camera. In the case of individuals who don’t own video-capable devices, officers contact family members and neighbors in order to verify the person’s whereabouts.

With many treatment and counseling services suspended during the pandemic, officers have also procured telemedicine contracts, so that individuals undergoing treatment for substance abuse and mental health issues can continue their programs while abiding by state issued stay-at-home orders.

“This is a stressful time for everyone,” Trevino said. “Many people under supervision have been laid off and are struggling to make ends meet. Our officers are working around the clock and checking in regularly with the people under their supervision, lending an ear to listen to worries and helping them get access to the resources they need.”

To reduce face-to-face interactions further, officers are using oral swabs and sweat patches to conduct drug-testing over a video call or in-person from a distance.

“We’re continually evaluating and improving procedures,” said Jonathan Hurtig, chief probation officer in the District of New Hampshire. “Some strategies are going to work and others won’t, but we’ll never know if we don’t try.”

A pretrial services officer in the Eastern District of Michigan checks a person’s whereabouts using location monitoring technology.

To efficiently absorb an influx of supervision cases resulting from compassionate release policies during the pandemic, officers stay in constant touch with judges and the Federal Bureau of Prisons. They also are deploying an array of location monitoring technologies, including ankle bracelets, voice-recognition systems, and smartphone-based GPS location monitoring applications.

The national Probation and Pretrial Services Office expects release numbers to grow throughout the pandemic. Compassionate releases, usually granted to older individuals or those with underlying health conditions, have increased over ten-fold since February, with the probation system taking on more than 100 additional cases in April and May.

“Each day presents us with a new set of challenges and we are continuously working to solve them,” Smith said. “We want the public to know that we’re dedicated to doing everything in our power to effectively and safely serve our communities, the courts, and the people who come before them.”

Subscribe to News Updates

Subscribe to be notified when the news section is updated.