As coordinator of courtroom interpreters for the Middle District of Florida, Darlene Knapp lives every day with a reality that few people consider. In federal courthouses across the United States, access to justice requires the use of languages spoken around the globe.

In the U.S. District Court in Orlando, where Knapp works, the roster of about 115 local contract interpreters represents many languages, including Spanish, Portuguese, Russian, and Mandarin.

But she sometimes must search for interpreters from elsewhere in the country when defendants speak less common languages. In recent years her searches have included Wayuu (a tribal language in Colombia), K’iche’ (a Guatemalan Mayan tongue) and lgbo (native tongue of the lbo people who reside primarily in southeastern Nigeria).

“We use interpreters daily,” said Knapp, who works to ensure that interpreters in her court meet the challenges of delivering hearings and trial testimony in two languages. “I try to be a resource for the interpreters, so that communications between limited English speakers and the court run smoothly.”

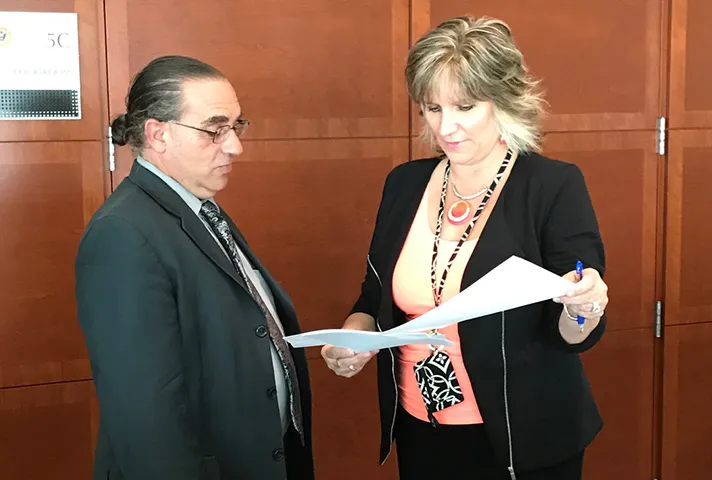

Darlene Knapp, shown speaking with Etienne Van Hissenhoven, a certified Spanish-language interpreter, says the local roster of interpreters in the Middle District of Florida can assist in trials in about 115 languages.

When a defendant with limited English proficiency, or who is deaf or hard-of-hearing, faces criminal charges, a skilled interpreter is more than a convenience. Like court-appointed attorneys, interpreters ensure a constitutional process, by enabling defendants to understand proceedings and assist in their own defense.

“Providing an interpreter is nothing less than access to justice,” said Javier A. Soler, Interpreting Program Manager with the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts. “We remove a big impediment by taking away the language barrier. Regardless of the legal outcome of a case, the bottom line is that meaningful access to the process was provided to the defendant.”

These defendants have received government-funded, court-appointed interpreters since 1978, when Congress passed the Court Interpreters Act, 28 U.S.C. § 1827.

More than 3,600 interpreters are registered in the judiciary’s National Court Interpreter Database, with expertise in over 180 languages, of which more than 120 are used regularly by courts. Most interpreters work as contractors hired for specific cases. Spanish accounts for roughly 96 percent of all interpreting requests, and around 100 Spanish interpreters are Judiciary employees.

| Language | Number of court proceedings |

|---|---|

| Spanish | 254,736 |

| Mandarin | 1,640 |

| Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian | 952 |

| Russian | 950 |

| Portuguese | 835 |

| Arabic | 815 |

| Cantonese | 538 |

| Korean | 403 |

| Vietnamese | 360 |

| Romanian | 340 |

In any language, court interpreting is a demanding professional skill. An interpreter must accurately capture a complex, unscripted legal process in two languages. When English is spoken, the interpreter renders everything for the defendant in real time—“simultaneous” interpreting. When the defendant speaks, the interpreter periodically interjects with English interpretations for the court—“consecutive” interpreting.

Since languages do not match up perfectly, court interpreters must develop extensive bilingual glossaries of legal and other terms. A major error can disrupt a trial, or even provide grounds for an appeal.

“Interpreting in court requires skills, dedication and continuous learning,” said Leonor Figueroa-Feher, another Interpreting Program Manager with the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts. “All your efforts pay off when you provide seamless communication across languages for the benefit of all parties.”

Because cases with Spanish language needs are so predominant, the Judiciary administers examinations to certify interpreters of Spanish. While federal judges make the final decision on appointing an interpreter, courts by law must use certified Spanish interpreters whenever they are “reasonably available.”

Soler said the certification test is challenging to reflect the demands of courtroom interpreting. The Judiciary, in turn, periodically reviews the testing process to reduce costs and maintain its integrity. Where interpreters once were graded in person by three-member judging teams, the candidates’ test responses are now digitally recorded and transmitted to test reviewers, which eliminates significant travel expenses.

The courts also play a direct role in locating qualified interpreters—which at times can seem like a specialized form of matchmaking.

Paula Gold, chief of interpreters at the Southern District of New York in Manhattan, said her court has an adequate number of certified interpreters to handle Spanish-language cases. But 15 percent of her interpreter cases involve languages other than Spanish, and those pose heightened challenges, Gold said.

In one case involving a native of Gambia, in west Africa, Gold hired two interpreters to relieve one another during a lengthy trial. But only one spoke the correct dialect of Mandingo, forcing him to handle the entire trial.

“We try to avoid one-interpreter trials, if possible,” Gold said. “After 35 to 40 minutes, fatigue sets in. The interpreter needed frequent breaks, but he did a spectacular job.”

Language skill is only part of the battle. Soler says that successful interpreters often are bi-cultural, as well as bilingual. They are impeccable note takers, and learn not to take emotional sides in a case. To preserve accuracy and transparency, interpreters’ ethical standards forbid them to change, summarize or censor what they hear.

“The rule is, if you hear it, you say it,” Soler said. “This means that the interpreter might have to render embarrassing or inflammatory statements without softening the meaning.”

Figueroa-Feher says that the interpreters, and the measures needed to make sure they are adequately prepared, are essential to the courts’ mission.

“Access to justice requires linguistic presence, not just physical presence,” she said. “You can be there, but it doesn’t mean you have any ability to help your case if you cannot communicate.”

Subscribe to News Updates

Subscribe to be notified when the news section is updated.