It is a ritual that has existed in some form since the birth of our Republic. Every four years, members of the Electoral College gather across the country to cast the votes that will choose the next president. The documents certifying those votes are sent to Congress for a final count, with additional copies going to the National Archives.

There is another less-known recipient of the Electoral College documents: the federal trial Courts.

Complying with laws dating back to 1792, one U.S. District Court in each state, as well as the District of Columbia, takes a set of Electoral College documents into its safekeeping, in case the originals get lost or invalidated. While the quadrennial role of the courts is forgotten to most Americans, it was seen as an important backstop in an era long before tracking numbers and bar codes.

"This goes back to the days when they didn’t have super reliable communications, and very important documents were being carried on horseback and by carriage," says Miriam Vincent, staff attorney for the National Archives and Records Administration. "There needed to be a federal holder, and in those days, the only consistent federal holder in every state was the U.S. courts."

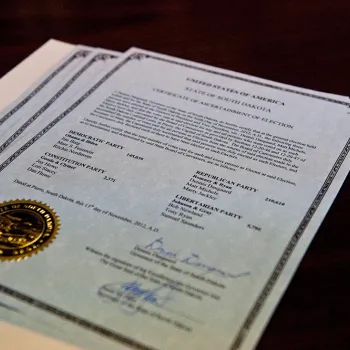

Electors will cast their votes on Dec. 17, and the final tallies of the 2012 Electoral College vote will be ratified before a joint session of Congress on Jan. 6. Two distinct documents, prepared by 50 governors and the mayor of the District of Columbia, validate key aspects of that vote. One document, a Certificate of Ascertainment, identifies the electors qualified to cast their votes for president. The second lists the final vote and is signed by each of the electors who took part.

Typically, Vincent said, the votes are cast in the capitals of each state, and the court documents are held in the nearest U.S. District Court. In practice, the primary documents have always arrived in Washington, and the courts have never been asked to produce their backup versions.

As a result, the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts gets occasional inquiries from court clerks about what to do with the Electoral College certificates. After one such inquiry in 2008, the AO sent out a national notice to federal court administrators reminding them of their role in the election process, and reissued that advisory after the November 2012 election. The 51 designated courts are required to keep the documents in a safe place. Under federal record disposition guidelines for United States district courts, courts may dispose of these documents six months after their date of issuance.

Although courts are less likely than ever to be asked to help validate a presidential election, Vincent said it is unlikely that Congress will remove federal courts from the process.

The courts' role, first outlined in 1792, was reaffirmed in an 1847 law, when Congress sought to regulate a free-form national election system, in which voting took place on different days in different states. While aspects of national elections are under review after 2012, Vincent said, talk of reform has focused on ways to reduce Election Day lines and possibly standardizing ballots for federal elections.

"There is still a need to do things on paper, and there is still a need for redundancy," Vincent said of the Electoral College certificates. "Some may see this as a relic of the 19th century, but the truth is that it’s worked since 1847. Congress has enough other things to focus on that I don’t know of any idea to monkey around with this at this point."

Subscribe to News Updates

Subscribe to be notified when the news section is updated.