In July 2013, Judge Julia S. Gibbons and W. West Allen, of the Federal Bar Association, prepare to testify in Congress about the impact of sequestration on federal courts.

Sequestration was a slow-motion fiscal catastrophe, erupting after two years of negotiation failed to prevent it. Starting in 2011, Congress mandated sharp spending cuts if an agreement to reduce budget deficits could not be reached. The universal expectation was that the dire consequences of sequestration would force Congress to compromise.

But on March 1, 2013, Congress did step off a “fiscal cliff,” and sequestration began. A day before the deadline, Judge Thomas F. Hogan, then-director of the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts (AO), notified federal judges that the Judiciary faced an imminent loss of $350 million. Similar crises raged across the federal government.

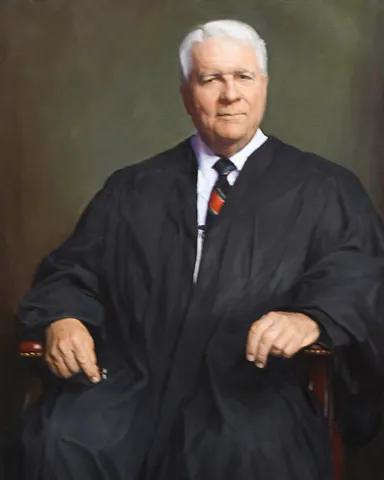

Judge Thomas F. Hogan

“It is becoming increasingly likely that Congress and the Administration will be unable to come to an agreement,” Hogan wrote. “Please be assured that we will continue to impress upon Congress the devastating impact of sequestration on the courts.”

Between July 2011 and January 2014, budget constraints, exacerbated by sequestration, reduced staffing in clerks of court and probation and pretrial services offices by nearly 3,300 positions – 15 percent of their total staff. The cuts also posed ongoing threats to the representation of defendants, treatment for individuals under court supervision, and the physical safety of court personnel. But by working together nationally to limit spending, the Judiciary rode out the crisis.

Sequestration was one of several budget emergencies in the last 25 years that underscore the dramatic ways financial governance has changed under the Judicial Conference of the United States, which recently celebrated its 100th anniversary.

In 2004, the Conference launched an ongoing cost-reduction campaign in the face of potentially crippling deficits. And in 2013 and 2018-19, the Judiciary continued operations through two government shutdowns. In each case, the Judiciary emerged with a deepened commitment to prudent spending.

“We’ve demonstrated that we are good stewards of the taxpayers’ dollars,” said Judge Julia S. Gibbons, former chair of the Conference’s Committee on the Budget. “We apply the same analytical skills that we use in deciding cases to making decisions about our budget and our approach to management.”

Chief Justice William Howard Taft persuaded Congress to create a national conference of judges in 1922. In 1939, a newly created Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts began drafting the Judiciary’s budget.

In 1922, Chief Justice William Howard Taft first convened the Conference of Senior Circuit Judges, which was the predecessor to the Judicial Conference. At that time, the Department of Justice administered federal court budgets, and it was all but impossible for the Judiciary to set national fiscal objectives.

In 1939, the newly formed AO took over budgeting duties, and some centralized budgeting worked well. But it became clear that efficiencies could be achieved by localizing some budgeting practices. Many spending decisions are made locally by 94 district courts and 13 judicial circuits, making coordinated national responses to budget crises challenging.

In more recent times, however, the Judicial Conference has provided centralized leadership when needed — often through the Executive Committee, with ongoing assistance from AO budget and other staff.

In March 2004, Judge Carolyn D. King, then chair of the Executive Committee, alerted Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist that rent costs were eating into program and salary budgets. Without change, growing numbers of employees would lose their jobs to pay for building space.

“Chief Justice Rehnquist didn't want to get involved in the day-to-day operations of the court system,” King said. “His answer was, ‘This is your responsibility. Get into it and come up with your recommendations about what we do.’”

By September 2004, just six months after King briefed Rehnquist, the Executive Committee, with direction and support from the AO Budget and Space and Facilities offices, presented an ambitious, wide-ranging plan, which the Judicial Conference approved. Known as cost containment, the Judiciary’s policy of restricting unneeded spending remains in effect to this day.

Judge Carolyn D. King

“We had to get down to our fighting trim, and we did,” King said. “The Judiciary’s money is not our money; it belongs to the taxpayers. So we’d better be very sure that we spend only the money we need to spend.”

Quickly, the Judiciary instituted a moratorium on new construction, until courthouse and office needs could be reassessed, so that space rent costs to General Services Administration (GSA) could be better controlled. Under the Judicial Resources Committee, the Judiciary explored new workforce measurement formulas that ensured more efficient and consistent staffing practices. Over time, technology increased the productivity of administrative staff.

King said the Conference also worked to educate federal judges about the budget process.

“The root financial problem for the Judiciary was that judges generally didn’t have basic information about the factors affecting our budget,” King said. “We had to get all judges up to speed – how it all worked.”

The Executive Committee’s strategy headed off a looming funding crisis. “Projected annual growth rates in most spending areas are lower than before cost containment,” a 2007 AO report said. “The anticipated gap between estimated budget requirements and funding levels has shrunk considerably.”

By early 2013, sequestration posed a very different challenge — surviving the abrupt loss of nearly $350 million in budgeted funds halfway through a fiscal year.

“A 5% across the board cut when you're not fully funded to begin with could have a devastating impact on the Judiciary,” said Judge Rodney W. Sippel, who was on the Executive Committee as sequestration approached.

In late 2012, Sippel and Judge Robert S. Lasnik, also an Executive Committee member, were directed to plan and oversee the Judiciary’s response to sequestration, if it occurred.

Several major cost areas were off limits, complicating the judges’ work. Rent payments to GSA were mandatory and, under the Constitution, judges’ salaries are protected. Budget experts had to focus on areas where spending could be cut or delayed, such as travel and training for judges and court staff, cyclical IT replacements, and drug and mental health treatment for individuals under supervision.

Sippel and Lasnik met regularly with AO budget experts, and the Executive Committee approved a package of emergency measures. While court budgets were reduced significantly, chief judges and court unit executives retained latitude to make local decisions about specific cuts.

“It was not without trauma, but when you look back on what happened, the courts continued to function,” Sippel said. “Trials continued to happen. Cases were continuing to move. I think from the public's point of view, the stress that we were under didn't keep the courts from their primary mission.”

Judge John D. Bates

Effective communication with Congress also was critical.

Judge John D. Bates, who became AO Director months after sequestration began, learned that some chief judges were drafting a letter to Congress, seeking to protect funding for federal public defenders.

“I reached out to those judges because I was concerned that the focus was a little too narrow,” Bates said. “I convinced them to take a broader approach, and that we should enlist more judges in the effort. We wound up with a several-page letter that touched on various consequences of sequestration. It still focused principally on the federal public defenders, but not exclusively.”

In the end, 87 out of 94 district chief judges signed the letter. “The members of Congress were receiving something from a judge in their state or district, and that made it more meaningful to them,” Bates said.

Confronted with the specter of ongoing budget cuts across the federal government, Congress enacted subsequent budget deals that prevented sequestration cuts to discretionary appropriations. Gradually, the fiscal threat posed by sequestration dissipated.

But throughout the emergency, the Judiciary had to make painful choices. In a few districts, criminal proceedings were halted on days when federal public defenders were furloughed. Court-appointed private lawyers, known as CJA panel attorneys, temporarily had their hourly rates cut, and payments were suspended altogether for the last three weeks of the fiscal year.

“Delaying payments on CJA vouchers to keep things going, that was painful,” Sippel said.

The Judiciary also worked together to maintain operations during two recent federal government shutdowns, in 2013 and 2018-19, as well as during a 21-day shutdown in 1995-96. The Judiciary sustained operations during these periods utilizing court filing fees and available balances from prior fiscal years. The record 35-day shutdown in 2018-19 nearly drained these resources.

James C. Duff

“We looked for every penny in every circuit so that we could keep the courthouses open,” said then-AO Director James C. Duff. “It was a magnificent example of coordinated teamwork, I think within the judicial branch and circuits, to be able to pull that off.”

Perhaps the most ambitious cost-containment initiative was launched in 2013, when the Judicial Conference approved a nationwide 3 percent reduction in courthouse and office space over a five-year period. The Conference also mandated that new court-related expansion must be offset by an equivalent reduction in existing space.

Judge D. Brooks Smith, who became chair of the Space and Facilities Committee in 2013, crisscrossed the country, urging circuit judges and administrators to meet their reduction targets.

In the end, courts met the goal, reducing offices, libraries, and court chambers — almost every type of court space except courtrooms. Reducing the amount of rentable court space continues to pay off annually, by limiting the growth in the Judiciary’s space rental costs.

“The folks in each circuit and in each court had to make this work, and they did,” Smith said. “This was a remarkably cooperative and well-coordinated effort for which all the administrators of our system deserve credit.”

Smith also noted that the campaign required a high level of collaboration among the three branches of government.

“I see the space reduction effort as a remarkable civics lesson for all of us,” Smith said. “The House committee monitored our progress closely, and the GSA provided consistent cooperation. We never could have reached our reduction goal if GSA had not agreed to take returned space off our rent bill.”

Judge John W. Lungstrum

The Judiciary is taking a proactive approach to its current budget challenges. After the Judiciary’s budget tightened considerably in recent years, the Executive Committee recently asked Judicial Conference committees to work with the Budget Committee to develop proposals that would help limit the growth of the Judiciary's budget without negatively impacting the judiciary's core mission.

This effort, known as the Strategic Budget Initiative, will take about two years to identify and evaluate proposals, and recommend any changes.

Judges said the Conference’s ability to effectively manage its own finances has been essential to protecting the Judiciary’s central mission, and to maintaining credibility when seeking funding.

“Cost containment is probably the Judiciary’s single most effective appeal to Congress, and that has made it a permanent feature of our budget process,” said Judge John W. Lungstrum, former chair of the Budget Committee. “That is the feedback we’ve gotten from our appropriators. They say, ‘We know the Judiciary is serious about containing costs, and that makes your budget request much more credible in our eyes.’”

Judicial Conference at 100

Learn about how the Judiciary’s national policy making body has grappled with many issues to mark the 100th anniversary of the Judicial Conference of the United States.

Subscribe to News Updates

Subscribe to be notified when the news section is updated.