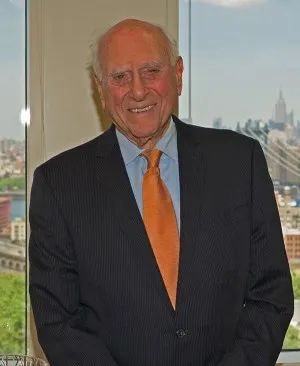

U.S. District Judge Jack B. Weinstein of the Eastern District of New York

Since the death of Judge Jack B. Weinstein on June 15 at age 99, his legendary life and legal career have been celebrated by fellow judges, who hailed him as a role model and champion of justice, and others of more humble standing who remember him as an “incredibly thoughtful” gentleman who stood up for “little guys.”

By any measure, Weinstein was a giant in the legal profession. A member of Thurgood Marshall’s legal team that prepared the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case, he was appointed by President Lyndon B. Johnson to the Eastern District of New York in 1967. In 53 years, until his retirement in 2020, he reinvented how courts handle mass tort litigation, greatly upgraded the role of U.S. magistrate judges, and conducted himself in an egalitarian manner, wearing business suits instead of a robe in the courtroom and often sitting at a table with defendants as he sentenced them.

“The Judiciary has lost a national treasure,” said Chief Judge Margo K. Brodie in a statement. She added that during his tenure as chief judge of the Eastern District, Weinstein “helped transform the Court into what it is today — a court that has served and continues to serve as a model of innovation in the administration of justice for the federal courts nationally.”

In a tribute in the New York Law Journal, lawyer Darryl M. Vernon recalled visiting a mob trial in Weinstein’s courtroom while attending law school. Weinstein recognized that Vernon and a friend were law students and invited them up to the bench, even permitting them to listen to sidebar conversations during the trial.

“It was an incredible experience and Judge Weinstein made it so,” said Vernon, who received his law degree from Yeshiva University in 1981. “He went out of his way to treat two law students that he didn’t know with the utmost dignity, consideration and thoughtfulness about how we might learn more before we became lawyers.”

Born in Wichita, Kansas, Weinstein moved with his family to Brooklyn as a child. He appeared as a young actor in a Broadway play and helped pay his way through Brooklyn College by working on the docks. In 1943, he joined the Navy and served in the Pacific on a submarine. Even in wartime, his sense of justice was evident.

Navy Lt. Jack B. Weinstein stands on the deck of the submarine USS Jalloa, in the Pacific theater.

While Weinstein remained proud of serving in “a great war for freedom,” he also harbored guilt, seven decades after the fact, for his submarine’s role in torpedoing and sinking a Japanese cruiser. “It had about a thousand Japanese sailors aboard. I’ve since thought about those men and their deaths, and regretted it, as I regret war generally,” Weinstein said in a 2014 video interview.

Weinstein graduated from Columbia Law School in 1948 and became a law professor there in the 1950s. Future Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was among his students, and a New York Times obituary of Weinstein noted that at a 2015 event, she “approvingly referred to him as ‘indomitable.’”

While teaching at Columbia, Weinstein assisted in researching and drafting the NAACP’s legal brief in Brown v. Board of Education. “My role was of the most minor degree,” he recalled with characteristic humility.

Serving in the Eastern District of New York’s Brooklyn courthouse, Weinstein became a recognized author in courtroom procedure. Starting in 1979, while presiding over a class-action lawsuit filed by Vietnam veterans exposed to the defoliant Agent Orange, he essentially rewrote the book on how federal courts manage mass litigation.

As recalled in a 2017 Moments in History video, Weinstein traveled around the country gathering testimony on the impact of Agent Orange, and then pioneered the use of court-appointed special masters to hear testimony from litigants. In 1984, as the case was nearing trial, the chemical companies settled by creating a $180 million reparations fund.

“The veterans were treated dreadfully at that time,” Weinstein said in an interview. “I as a veteran had a great deal of empathy for them.”

While some critics painted Weinstein as overreaching in his approach to mass tort litigation, his process was replicated in federal courts around the country. Weinstein personally presided over mass torts cases involving manufacturers of asbestos, the anti-miscarriage drug DES (diethylstilbestrol), tobacco products, and handguns.

“The things that Judge Weinstein has done in the world of mass torts has had implications far beyond his courtroom,” said Les Fagen, who served as a law clerk for Weinstein. “He developed a body of law for how to settle and resolve mass torts which other courts and other litigants are following.”

Weinstein’s management of the Agent Orange case had a more personal impact for Phillip Case, a Vietnam veteran. “Thank God for people like Judge Weinstein,” he said in 2017, “because little guys like us didn’t stand a chance.”

A statement from the Eastern District of New York, where Weinstein served as chief judge from 1980 to 1988, provided a long list of his innovations.

“He transformed the way in which magistrate judges were utilized in case management, raising their experience, profile, and visibility in ways that attracted increasingly qualified individuals, a trend replicated nationally,” Chief Judge Brodie wrote.

“He oversaw the implementation of a court-annexed arbitration and mediation program, a novelty at the time that has become a model for the rest of the country and, indeed, the world; he created the Eastern District Pro Bono Panel and the Eastern District Civil Litigation Fund to support pro bono representation of civil litigants, another innovation that was soon copied in other federal and state courts; and, in keeping with his concern that indigent persons be properly represented, he created the Criminal Justice Act Committee to ensure that the Constitutional guarantee of a right to representation in criminal cases is meaningfully afforded to indigent defendants.”

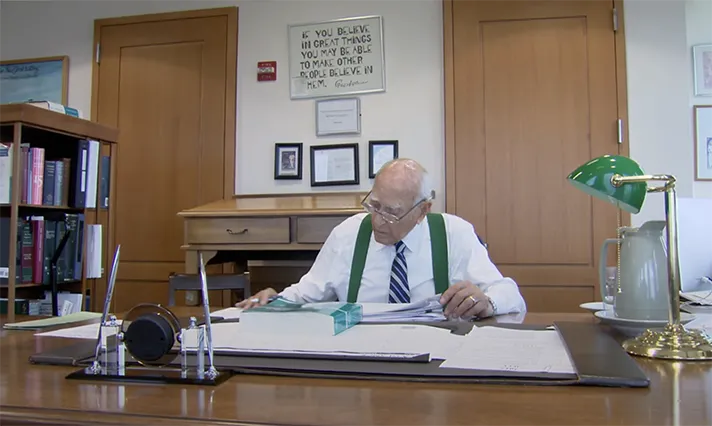

A widely respected expert on legal procedure, Weinstein said he wanted to be remembered for helping individuals to “avoid the life-killing environment of prisons.”

Weinstein also was a prolific scholar who wrote several books, including such legal profession standards as the multivolume New York Civil Practice and Weinstein’s Federal Evidence.

In and out of court, Weinstein embraced an everyman informality aimed at putting people at ease in a courtroom. He wore a suit into court and sometimes stepped away from the bench so that he could see proceedings from the viewpoints of others.

At a June 18 memorial service, Weinstein’s oldest son, Seth, recalled that “he sentenced people sitting not from the high bench but across the table. Explaining to them what the sentence was, what it was for, and how they could redeem their lives.”

In 2017, the Eastern District dedicated its ceremonial courtroom in Brooklyn in Weinstein’s name, and in 2020, at the age of 98, he retired as a judge.

“I would like to be remembered for trying to work with individuals to help them avoid the life-killing environment of prisons,” he told the New York Times, “and to save them for a life with relatives and friends, with a job, and with the opportunity to lead a lawful life.”

Weinstein’s wife of 66 years, the former Evelyn Horowitz, died in 2012. Two years later, he married Susan Berk. In addition to his wife, survivors include three sons from his first marriage, Seth, Michael, and Howard Weinstein; two stepchildren, Ronnie Rosenberg and Stephanie Berlin; and two grandchildren.

Judge Jack Weinstein and Mass Tort Litigation

Five NY Judges Remain a Brotherhood 70 Years After Serving in WWII

Subscribe to News Updates

Subscribe to be notified when the news section is updated.