For many on the Louisiana and Texas Gulf Coast, Hurricane Laura quickly escalated from a mild to a terrifying storm, slamming into the shore on Aug. 27 at winds of nearly 150 miles per hour. Then, almost as suddenly, the hurricane weakened and moved on. So did national media interest.

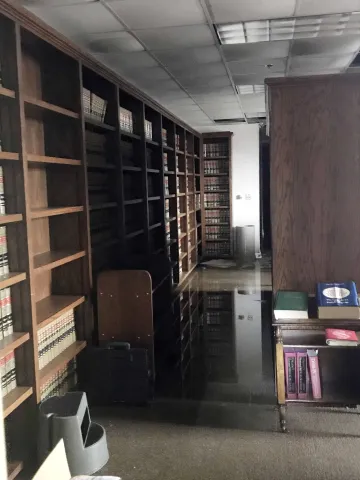

After walls and a section of roof were torn away, wind-driven rain caused severe water damage throughout the courthouse in Lake Charles, leaving standing water in the library.

For those caught in Laura’s path, however, there was nothing modest, or even temporary, about the storm, and one conspicuous casualty has been the federal courthouse in Lake Charles, Louisiana. Laura’s record winds, which knocked down thousands of power poles, also ripped large sections of rooftop and wall from the courthouse. All four courtrooms and chambers were flooded by wind-driven rain. The building could be closed for a year or more.

There also is lingering human impact. Like other residents of Lake Charles, a city of about 70,000 in Western Louisiana, many of the courthouse’s employees, including the federal district judge and the magistrate judge serving there, suffered major home damage. They also could face months or longer of dislocation.

“Many people just recently were able to return to their homes. They still don’t have power. They don’t have sewage. You can’t even flush a toilet,” said Chief Judge S. Maurice “Maury” Hicks, Jr., of the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Louisiana. “What will they return to? What kind of condition will their houses be in? How much mold? How much mildew? When can they get repairs made?”

Despite the disarray, the court community has worked to create its own silver linings. Other federal court districts in Louisiana and Texas have offered court space so that judges and employees can continue to work. Probation officers as far away as Ohio and Alaska have sent emergency supplies and gift cards to their colleagues in Lake Charles.

U.S. District Judge James D. Cain, Jr.: “The court family has been just tremendous. Every judge in our district was reaching out to me, basically saying, ‘Do you need a place to stay?’ ”

District Judge James D. Cain, Jr., and his wife experienced the generosity firsthand. When their house suffered major roof and water damage, they were taken in for three nights by fellow District Judge Robert R. Summerhays in Lafayette, a town 70 miles from Lake Charles that suffered minimal impact. Cain is currently living on another judge’s property while they look for a rental.

“The court family has been just tremendous,” Cain said. “Every judge in our district was reaching out to me, basically saying, ‘Do you need a place to stay?’ Our house is not livable. My contractor has told me it will be six to eight months before we can go back.”

Just days before the storm hit, there was little warning of its severity. By the time Laura reached land at Cameron Parish, it was a Category 4 hurricane, and Lake Charles was under a mass evacuation order. When he and his wife returned home two days after the storm, Cain realized how devastating the winds were.

“My wife gets very sad when we go back. There is literally not a building in Lake Charles that isn’t damaged,” Cain said. “We had all these beautiful oak trees. Every tree is snapped in two.”

Added Hicks: “The scale and extent of the destruction cannot be comprehended until you see it in person.”

The constant hurricane threat along the Gulf Coast has created a culture of camaraderie, mutual support and resilience among the federal courts in Louisiana, Texas, and Mississippi.

In 2005, the Western District of Louisiana provided makeshift court space to judges from the Eastern District of Louisiana who were forced to evacuate by Hurricane Katrina. They did the same for the Eastern District of Texas in 2017, when major flooding closed the Beaumont, Texas, federal courthouse and banished court staff from their homes.

Probation staff from the eastern districts of Louisiana and Texas recently returned the kindness, arriving with SUVs full of clothing and household supplies. For several hours, a parking lot near the ravaged Lake Charles courthouse became the scene of an emergency giveaway for probation staff in Lake Charles and to the former offenders who are under the staff’s community supervision. With racks of clothing, and boxes of cleaning and other supplies, the parking lot took on the feel of an outdoor store.

“We have also benefited from the aid and assistance from our brothers and sisters in the federal probation system with our own natural disasters,” said Myra A. Kirkwood, chief U.S. Probation officer for the Eastern District of Texas, whose staff suffered major property losses during Hurricanes Rita, Ike, and Harvey. “It was only natural for us to offer and render assistance without a second thought, and to specifically target our defendant and persons under supervision populations. Nothing brings us more satisfaction than trying to help the most vulnerable in a tragic situation.”

Jay Garner, chief U.S. Probation officer for the Western District of Louisiana, said he and his staff and have been deeply moved by the support.

“It’s been overwhelming, not just the storm but the generosity exhibited by other offices and chiefs,” Garner said. “They have been so generous, it’s difficult to put into words.”

As families settle into their new reality, the court is working out the logistics of transferring its operations. Cain has shifted his court to the federal courthouse in Lafayette, while it is determined whether the existing leased courthouse in Lake Charles can be rehabilitated.

Chief Judge S. Maurice “Maury” Hicks, Jr.: “The destruction cannot be comprehended until you see it in person.”

The probation staff already had been working remotely because of the coronavirus (COVID-19), and individuals under their supervision are required to provide an evacuation plan specifying where they will go in the event of an emergency. Contact has been reestablished with probation officers, Garner said, and one group of sex offenders was evacuated before the storm to a new location in Tyler, Texas.

But as other hurricanes gather attention, the recovery work in Lake Charles will take a long time, both for the courthouse and the community.

Hicks, who furiously out pedaled a fast-approaching Hurricane Betsy when he was 13, has been through many major storms since, as has the Gulf Coast area. He says the court staff and other residents are ready to rebuild but will need help. Contractors and supplies, he worries, will be in short supply for a region that will need a massive repair and cleanup.

“These people have been through disasters before. They know it’s going to happen, yet they survive,” Hicks said. “Lake Charles will again get up on its feet and go. How long will it take? Your guess is as good as mine. New Orleans took 10 years before things normalized after Katrina. I think we’ll probably see the same thing for Lake Charles.”

Subscribe to News Updates

Subscribe to be notified when the news section is updated.