Judge Frank M. Johnson Jr. faced death threats while desegregating schools and public transit.

It was a turning point for a young pastor named Martin Luther King Jr.—and for a young federal judge named Frank Minis Johnson Jr.

In December 1955, as a bus boycott roiled Montgomery, Alabama, King was elected leader of the city’s fledgling protest movement. A month later, Johnson was appointed U.S. district judge in Montgomery’s federal courthouse.

For the next decade, Johnson’s court, the Middle District of Alabama, played a critical role in the civil rights movement, and in two of King’s most defining hours—the Montgomery bus boycott and the 1965 Selma marches.

As the nation celebrates King’s birthday, Johnson’s successors on the bench still take pride in a time when protesters and judges alike braved threats of violence, as they challenged racial segregation.

“It is a critical part of our court’s history,” said W. Keith Watkins, chief judge of the Middle District of Alabama, who is leading continuing efforts by the court to pass on lessons from the civil rights era. “In Alabama, race was the issue. It’s difficult to exaggerate how bad it was for blacks.”

King and Johnson were newcomers to Montgomery on Dec. 1, 1955, when Rosa Parks was arrested for defying Montgomery’s segregated-bus rules.

In defending the boycott, King invoked the federal courts, which in 1954 struck down school segregation. “If we are wrong, the Supreme Court is wrong,” he said. “If we are wrong, the Constitution is wrong. If we are wrong, God Almighty is wrong.”

When four riders sued in the Middle District of Alabama, a special three-judge panel, with Johnson and Judge Richard T. Rives in the majority, ruled in Browder v. Gayle that segregated buses violated the 14th Amendment. In December 1956, after the Supreme Court upheld the ruling, the yearlong boycott ended in a historic civil rights victory.

It was the first of numerous landmark cases. Johnson and his colleagues struck down rules denying voting rights to blacks, desegregated Montgomery’s bus depot and airport, and in 1963, ordered Alabama public schools desegregated.

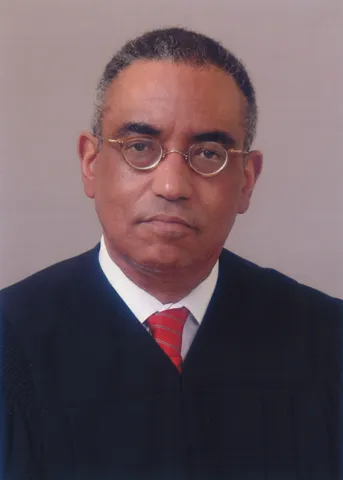

Judge Myron H. Thompson said the federal court was "an oasis" for blacks in Alabama.

The court’s fairness made it an “oasis” for Alabama blacks, said Judge Myron H. Thompson, who succeeded Johnson in 1980, after Johnson became an appellate judge.

“The federal court in Montgomery, Alabama, was virtually an island. It was the only place where blacks in the state could go and be assured that they were American citizens,” Thompson said. “Judge Johnson exemplified the essence of judging. He was an example for all judges, not just me.”

In 1965, Johnson and King crossed paths again. The first of three voting-rights marches, from Selma to Alabama’s statehouse in Montgomery, ended in violence on March 7, 1965, when deputies beat protesters as they crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

Asked to halt police harassment, the judge initially prohibited another bridge crossing until both sides could arrange to protect the protesters.

After learning that President Johnson would nationalize Alabama’s National Guard, the judge permitted King and the marchers to cross the Pettus Bridge. His order barred Alabama authorities from “arresting, harassing, thwarting or in any way interfering with the effort to march from Selma to Montgomery.”

Johnson received death threats, and the Ku Klux Klan dubbed him “the most hated man in Alabama.” A cross was burned on his lawn, and a firebomb damaged his mother’s house. He had constant U.S. Marshal protection for 15 years.

Johnson, who later won the Presidential Medal of Freedom, said his only goal was to enforce the Constitution. “The action of the judges, sitting on the federal bench, hasn’t been for the purpose of effecting social change,” he said in a 1974 interview. “I approach the thing strictly from a legal standpoint. … I have no interest in social change, as a judge.”

Chief Judge W. Keith Watkins hopes that the court's civil rights legacy can educate younger generations.

King had a more expansive view. According to Johnson’s New York Times obituary in 1999, King said the judge had given “true meaning to the word ‘justice.’”

Watkins hopes that the court’s civil rights legacy can educate younger generations, who have no direct memories of King or Johnson. He believes that King and the judge taught important civic lessons on how the rule of law is essential to freedom.

“Most of the lawyers coming out of school today have to learn about this from a book, like I have to learn about World War I,” Watkins said. “It’s really not well known how bad it was, or how much courage it took to take on the task.”

The court’s judges have worked to preserve the Middle District of Alabama’s history, especially with regard to civil rights.

In 2011, Thompson and Judge W. Harold Albritton hosted a luncheon with former Freedom Riders and John Patterson, Alabama’s governor in the early 1960s.

Thompson led efforts to restore a dilapidated bus depot where Freedom Riders were severely beaten. Today, the depot, located next to the court, is a museum run by the state. Thompson also restored Johnson’s old courtroom and chambers, where he works today, so that visitors can see them as they were in the 1950s and ‘60s.

“This court has a special place in history,” Thompson said. “There’s not just pride, but also a responsibility. It places a lot on our shoulders to make sure that that history is preserved.”

Rosa Parks — Ride to Justice

Learn about Civil Rights hero Rosa Parks and four other women, also forced off city buses, and how their courage led to a federal court decision to strike down segregation on buses. Find out more in the Rosa Parks Collection at the Library of Congress.

Subscribe to News Updates

Subscribe to be notified when the news section is updated.