As a federal judge in South Carolina, J. Waties Waring initially made few waves. Then in the mid-1940s, he had an epiphany that shook his life, his state, and American racial history. Segregation, he concluded, was not just wrong, but unlawful.

Ignoring physical threats and the rage of lifelong friends, Waring issued a series of decisions attacking Jim Crow laws, eventually firing a first, loud shot in a case that helped lead to Brown v. Board of Education. But when he left the bench in 1952, Waring was rapidly forgotten by history.

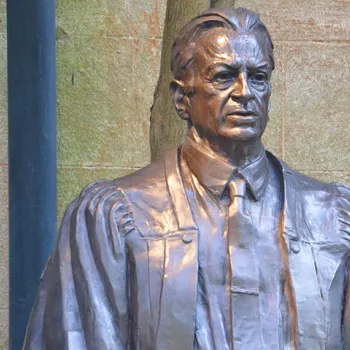

On April 11, Judge Waring’s legacy was reclaimed, with a statue honoring his memory. The ceremony was inspired, in part, by a U.S. district judge who sits in the same Charleston courthouse where Waring once caused such a storm.

“Judge Waring had an extraordinary legacy,” said U.S. District Judge Richard M. Gergel, who has closely studied and helped educate the public about Waring’s career. “Charlestonians, and the bar, were blown away that we had a true civil rights hero in our midst. They thought it was embarrassing that he had never been honored.”

Joining in the ceremony were U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder, nine judges from the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, all of South Carolina’s U.S. district judges, and the chief justice of South Carolina’s state supreme court.

During his tenure, Judge Waring issued decisions that ordered equal pay for African American school teachers in South Carolina, gave African Americans access to a state-funded law school, and permitted African Americans to vote in the state’s party primaries. He also integrated his courtroom staff.

According to accounts, Judge Waring was shunned by Charleston society. Chunks of concrete were hurled through his windows, and burning crosses were planted on his lawn. Waring’s second wife, a Northerner, was spat on, Gergel said.

In 1951, Briggs v. Elliott, a school education case with national implications, came to Judge Waring’s courtroom. According to historical accounts based on court transcripts, Waring challenged Thurgood Marshall, NAACP lawyer and future Supreme Court justice, to recast his case, so that it would pose an explicit constitutional challenge to the doctrine of “separate but equal,” which had sustained segregation since the 1896 decision in Plessy v. Ferguson.

Gergel said Waring was mindful of two 1950 Supreme Court rulings that had struck down racial barriers in higher education. Under similar reasoning, Waring believed, the Supreme Court would overturn segregation in public schools. A three-judge federal panel upheld South Carolina’s segregation laws, but Judge Waring, a member of the panel, wrote a fiery dissent. He argued that segregation violated the 14th Amendment guarantee of equal protection under the law.

“Segregation in education can never produce equality,” Waring wrote. “It is an evil that must be eradicated.”

At the Supreme Court, Briggs v. Elliott was the earliest of five school segregation challenges that were folded into Brown v. Board of Education. Waring’s core reasoning, that “segregation is per se inequality,” was directly echoed in the high court’s 9-0 landmark ruling.

“It was as if he knew where the court was going before the court did,” Gergel said.

Waring died in 1968 in New York, after moving there with his wife. Gergel, a native South Carolinian, said he had never heard of Waring until reading his name in a history of the early civil rights movement. He continued to learn more, and when Gergel became a federal judge in 2010, he posted Judge Waring’s framed oath of office in his chambers.

In 2011, the 60th anniversary of Briggs v. Elliott, Judge Gergel co-authored an opinion column called “The Dissent That Changed America.” A legal seminar in Charleston, under the same title, further stirred appreciation for Waring’s career, Judge Gergel said.

Local lawyers established an educational website honoring Judge Waring’s legacy, and began raising money for the statue unveiled Friday outside the U.S. District Court in Charleston.

“This is about the rule of law,” Gergel said. “Judge Waring gave up comfort and standing for what he felt the law obligated him to do. All of my colleagues look at his legacy with great admiration.”

Read more about the Judge J. Waties Waring Statue Dedication ceremony.

Subscribe to News Updates

Subscribe to be notified when the news section is updated.