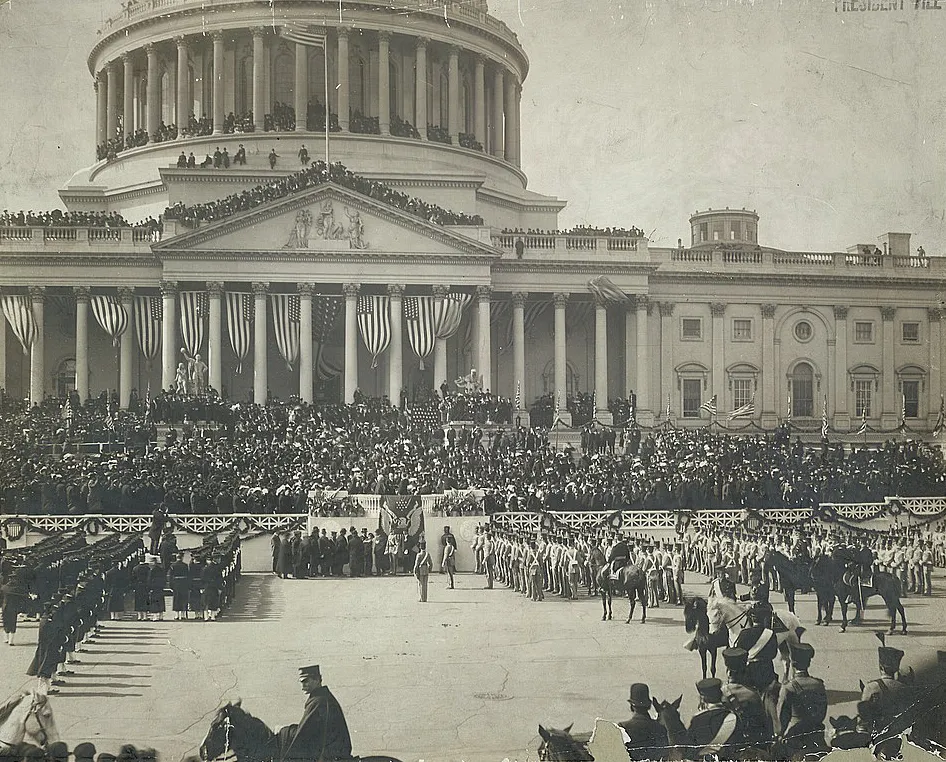

Chief Justice Melville W. Fuller administers the oath of office to Theodore Roosevelt during his second swearing-in, in 1905.

With the swearing-in this week of President Obama, U.S. Presidents have taken the oath of office 65 times in our nation’s history, and a federal jurist has administered that oath on 62 of those occasions.

No constitutional or statutory language mandates that the federal Judiciary be involved; the only qualification is the legal authority to administer an oath. Nevertheless, 15 of history’s 17 chief justices, one Supreme Court associate justice, an appeals court chief judge, and two U.S. district judges have participated.

The tradition of the federal Judiciary’s participation began when Associate Justice William Cushing swore in George Washington in Philadelphia to begin his second presidential term in 1793. (In 1789, Washington had been sworn in by Robert Livingston, a state judge, in New York City.)

Chief Justice Oliver Ellsworth swore in Washington’s successor, John Adams, in 1797, the first of 57 times that chief justices have administered the oath. Chief Justice John Marshall holds the record, with nine. Chief Justice Roger Taney is next, with seven.

The first two chief justices — John Jay and John Rutledge — never swore in a president. But beginning with Ellsworth, no chief justice has missed a scheduled Inauguration Day swearing-in. Presidential deaths gave rise to the six other occasions when a chief justice did not administer the 35-word presidential oath contained in Article II of the Constitution.

William Cranch, chief judge of the U.S. Circuit Court in the District of Columbia, swore in John Tyler as president in 1841, and Millard Fillmore in 1850 after the deaths of Presidents William Harrison and Zachary Taylor, respectively.

U.S. District Judge John Hazel (of the Western District of New York) administered the oath to Theodore Roosevelt in 1901 after President William McKinley’s assassination. When Calvin Coolidge became president after Warren Harding’s death in 1923, his father John, a notary public, administered the oath at the Coolidge family home in Plymouth, Vermont. And U.S. District Judge Sarah Hughes (Northern District of Texas) swore in Lyndon Johnson in 1963 after President John Kennedy was killed. Judge Hughes administered the oath aboard Air Force One before it took off from Dallas’s Love Field airport.

On two other occasions, a president could not complete a term of office. Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase swore in Andrew Johnson in April 1865, following the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln, and Chief Justice Warren E. Burger swore in Gerald Ford in August 1974, after the resignation of President Richard M. Nixon.

A few presidents have taken oaths in both private and public settings. Chester A. Arthur was sworn in by New York Justice John R. Brady in a private 1881 ceremony, following President James Garfield’s killing. Two days later, he also took a public oath, administered by Chief Justice Morrison Waite.

Repeated oaths are not included in the total of 65 presidential oaths. This scenario occurred most recently this week, when President Obama was sworn in privately at the White House on Sunday, Jan. 20, the day his first term concluded, before taking his public oath on Monday, in the traditional Capitol ceremony.

The federal Judiciary’s participation in swearing in the nation’s vice presidents has not been as frequent. Starting with Chief Justice Marshall’s administering the oath to Vice President George Clinton at the start of Thomas Jefferson’s second administration, federal jurists have sworn in vice presidents 16 times.

The recent trend, however, is toward greater frequency. The chief justice or an associate Supreme Court justice has participated in six of the last seven vice presidential swearing-in ceremonies—including this week, when Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor administered the oath to Vice President Biden. She did so privately on Sunday, and again at the public ceremony on Jan. 21.

You can access information compiled by the Architect of the Capitol curator’s office about presidential oaths — and who administered them — on the Library of Congress' website.

Subscribe to News Updates

Subscribe to be notified when the news section is updated.